Follow links for updatesDue to COVID-19 and the associated workload I am unable to keep this blog up to date. Please visit wcs.org/coronavirus and oneworldonehealth.wcs.org for updates on our ongoing work and related activities.

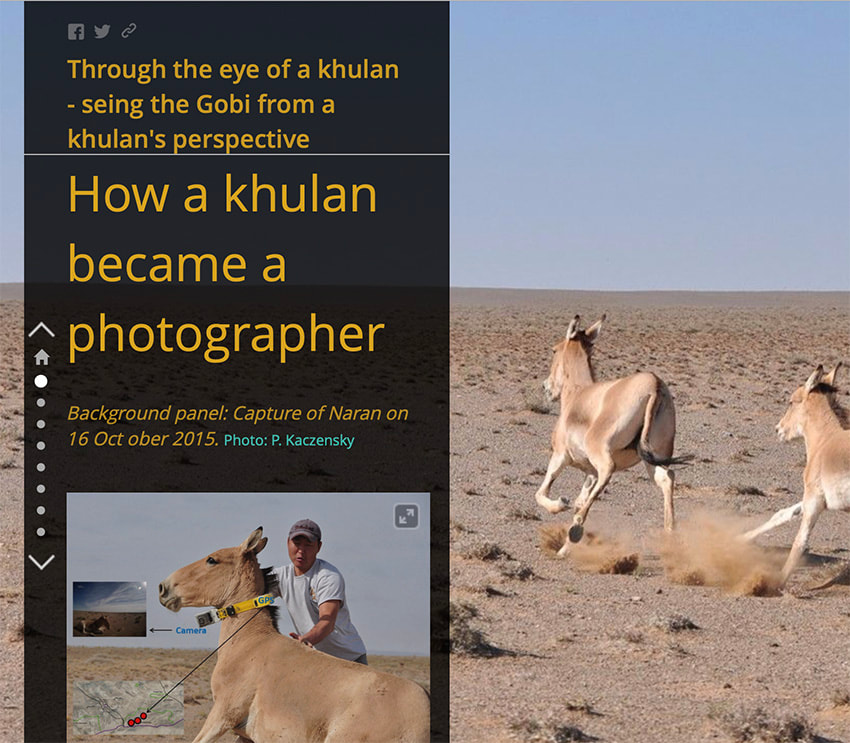

Take care, stay safe and sane! Chris and PK See and read more about the application of the camera collar in the Gobi on this ArcGis StoryMap, with great background information and beautiful photos.

Link to the StoryMap in English Link to the StoryMap in Mongolian The Mongolian Gobi-Eastern Steppe Ecosystem is one of the largest remaining natural drylands and home to a unique assemblage of migratory ungulates. Connectivity and integrity of this ecosystem are at risk if increasing human activities are not carefully planned and regulated. The Gobi part supports the largest remaining population of the Asiatic wild ass (Equus hemionus; locally called “khulan”). Individual khulan roam over areas of thousands of square kilometers and the scale of their movements is among the largest described for terrestrial mammals, making them particularly difficult to monitor. Although GPS satellite telemetry makes it possible to track animals in near-real time and remote sensing provides environmental data at the landscape scale, remotely collected data also harbors the risk of missing important abiotic or biotic environmental variables or life history events. We tested the potential of animal borne camera systems (“camera collars”) to improve our understanding of the drivers and limitations of khulan movements. Download the open access paper here.

A short film the Wildlife Conservation Society recently premiered, One Planet That Sustains Us All, produced by the WCS in-house video team Natalie Cash and Jeff Morey, asks the provocative questions: “Have we humans evolved enough as a species to protect the air we breathe? The water that gives us life? The soils that feed us?”

A story referring to CSN and WCS by Jennifer S. Holland from the from National Wildlife magazine and the National Wildlife Federation

https://www.nwf.org/Home/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2019/Feb-Mar/Conservation/Wildlife-Disease  We’ve just returned from two remarkable weeks in (Republic of) Congo. There we visited WCS teams in Libonga, Bomassa, and Mondika. At the latter site, we were privileged enough to see habituated gorillas as they went about their daily routine. This extraordinary opportunity reflects years of effort on the part of trackers and research assistants, who have devoted themselves to gaining the trust of two local (and now habituated) gorilla troupes. There are only three such sites in the whole of the western gorilla habitat within Central Africa. All this has taken place on the backdrop of ever-advancing logging and mining infringement. We were shepherded to the to the remote campsite by nimble and patient guides who tempered their pace to accommodate ours, pointing out scat from leopards, duiker and elephants along the way. Thanks to the tireless and knowledgeable Mondika team, we were then escorted through the florid forest to the gorillas’ home turf. As they adeptly cut their way through dauntingly dense bush, our chaperones expertly guided us to the best viewpoints while whispering individual information about each gorilla we encountered. Initially, we met a cheeky youngster, bouncing rebelliously away from his mother’s protection. He exhibited the uncanny gorilla knack of looking simultaneously indifferent and inquisitive as he considered us. Later, we were astounded by a silverback’s voluptuous buttocks precariously saddling a slender branch 15 metres off the ground. Much to our delight (and relief) he swiftly and effortlessly descended from his improbable perch to join the group below. To see these magnificent creatures ‘at home’, relaxed in their natural environment, curiously observing us, was an incomparable and unforgettable gift. We were told that a silverback in a habituated group appears to live longer than an unhabituated individual - perhaps because of satellite human activity that discourages other gorillas from challenging him. Furthermore, these animals may, on some level, comprehend this advantage. So a spirit of cooperation is in the air—gorillas cede some privacy in exchange for some protection.There is a valuable lesson here: sharing the environment, respecting all those that constitute and contribute to it, patiently working together - this mutual respect can promote balance and harmony in any circumstance. As we bid farewell to the old year and welcome a new one, let us all strive for better appreciation of our neighbours and understanding of our environments- local and global. May we appreciate all the amazing creatures in our midst and aim to protect the planet that we share. -pk We often report on exciting and successful wildlife stories from afar, and this is certainly fun. However, in reality, much of our work is not in the least bit glamorous and fun. More often than not we are gathering information from behind our desks, endlessly staring at computer screens, and trying to connect with potential donors. Subsequently we travel through a multitude of airports with their endless security and immigration checks and on airplanes whose reliability decreases logarithmically with the distance from the starting point. Once on site, it is surprising how many conditions must necessarily align for us to actually get the work done. Many aspects are beyond our control, weather and the behaviour of the wildlife for one, but others like the relationships with administrations and project partners initially appear sound and solid but then spiral out of control. When things just do not want to align, you first and foremost want to have a great team with you at the field site. Good humour, coffee with fatty and sugary foods and the odd stiff drink during cold dark nights go a long way. Here a rare story on a failure in Kazakhstan earlier this year from the BBC: read more Team waiting for days in a ranger station for kulan to be successfully captured - good food and and general good cheer go a long way in situations like this.

Collaring of khulan (Equus hemionus, https://lnkd.in/dzA4Yjv) to assess potential impacts of mining related infrastructure development and other anthropogenic developments in the southern Gobi of Mongolia (https://lnkd.in/dNYGYed). From 16-24 September 2018, a total of 30 khulan, 18 mares and 12 stallions, were successfully anaesthetised and collared. All animals were fitted with GPS-Iridium. Here a video showing the reversal of anaesthesia and release of a male khulan with a collar

The 2017 Conservation Impact Report from the Wildlife Conservation Society is available for download here

|

PK, Chris & FriendsPeriodic musings Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed